Introduction

The ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) salts are anticoagulants widely used in laboratory diagnostics, especially for hematological testing and for stabilizing the blood for assessment of unstable and fragile molecules such as cytokines, peptides and cardiac biomarkers (1). The leading principle underlining the use of EDTA as an anticoagulant relies on its ability to irreversibly sequester (i.e., chelate) divalent ions such as magnesium, manganese, zinc and calcium, with the last ion exerting an irreplaceable function in the physiological process of blood coagulation (1). This favourable property may turn out to be a challenge under some circumstances, especially when serum or plasma used for analysis of a number of clinical chemistry and coagulation tests are inadvertently contaminated by this additive. On this assumption, the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) currently encourages the use of a specific “order of draw” when collecting blood specimens, which specifically entails the collection of EDTA-containing tubes at the end of the sequence (2). This recommendation is essentially based on anecdotal evidence, as well as on a series of outdated case reports which described substantial bias of calcium and potassium after cross-contamination of potassium (K)2-EDTA or K3-EDTA between tubes collected for haematological testing and the following serum tubes (3,4). In another article, we reported the occurrence of spurious hyperkalemia and hypocalcemia due to inadequate phlebotomy procedure, that led to K2EDTA contamination from a blood tube and a needleless blood gas dedicated-syringe containing 80 I.U. lithium heparin (5). This evidence has been convincingly contradicted by data reported in recent studies, showing that results of coagulation tests and of those clinical chemistry parameters that are more vulnerable by cross-contamination of ion-chelating additives (i.e., potassium, sodium, calcium, magnesium and phosphate) are not significantly biased by a casual order of draw (6-10).

Regardless of whether or not a casual order of drawing blood tubes should be regarded as a real problem or a myth, it is unquestionable that the contamination of serum or lithium heparin blood with EDTA salts dramatically impairs the quality of testing and, when unrecognised, may jeopardize patient safety and waste healthcare resources. The major problem of EDTA contamination in diagnostic testing emerges from a direct chelating effect on divalent ions, as well as from the potential introduction of potassium (and sodium, to a lesser extent) contained in the EDTA salts (1). It is also noteworthy that EDTA contamination seems to occur more frequently than conventionally assumed in routine laboratory practice. A recent study reported that EDTA-contaminated samples were the cause of 14.3% cases of hypocalcaemia, 4.8% cases of hypomagnesaemia, 3.1% of hyperkalemia and 1.4% cases of hypozincaemia (11). The major sources of serum or plasma contamination by EDTA were then identified as backflow when collecting blood using evacuated tube systems, decanting of blood from EDTA containing tubes, and droplet transfer of EDTA blood via a syringe tip (11).

The effect of EDTA salts contamination on clinical chemistry testing has been reported in some epidemiological investigations (11,12), but it has not been precisely estimated in an experimental study. As such, the aim of this investigation was to evaluate the effect of lithium heparin sample contamination with different amounts of K2EDTA blood, by assessing a panel inclusive of the most frequently requested clinical chemistry tests in our institution.

Materials and methods

Study population

The study population consisted in 15 volunteers (mean age 48 years, range 33–60 years; 5 males and 10 females), enrolled among the laboratory staff (i.e., 74 subjects). Blood samples were collected at rest, after an overnight fast, between 8 and 9 AM by a single and experienced phlebotomist and following the CLSI H03-A6 document with minor modifications (13). Each patient provided an informed consent for being enrolled in this study, which was in accord with the ethical standards established by the institution in which the experiments were performed and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Study design

According to our experimental design, 3 sequential blood tubes (Becton Dickinson Italia, Milan, Italy) were collected from each volunteer, as follows:

- Two lithium-heparin blood tubes tube without gel (13 x 110 mm, 6.0 mLBD Vacutainer® plastic whole blood tube without gel containing lithium-heparin 102 I.U.; Ref. 368886).

- One K2EDTA blood tube (13 x 75 mm, 3.0 mL BD Vacutainer® plastic whole blood tube containing 3.4 mg of spray-coated K2EDTA; Ref. 367835).

All blood tubes were filled up to the nominal volume, and all phases of sample collection were accurately standardized. The two lithium-heparin tubes of each subject were pooled to obtain 12 mL of heparinised blood, which was then divided in 5 aliquots of 2 mL each. The whole blood of the K2EDTA tube was then added in scalar amount to the autologous heparinized aliquots, to obtain different degrees of K2EDTA blood volume contamination (Table 1). The aliquots were then mixed by gentle inversion and centrifuged at 1300 x g for 10 min at room temperature. The following clinical chemistry parameters were then measured in all aliquots using the same Roche cobas 6000 c501 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany): alanine aminotranspherase (ALT), bilirubin (total), calcium, chloride, creatinine, iron, lactate dehydrogenase (LD), lipase, magnesium, phosphate, potassium and sodium. All parameters were measured in one single analytical run according to manufacturer’s specifications and using proprietary reagents with the same lot number. The analyzer was also previously calibrated against appropriate proprietary reference standard material and verified by means of third-party internal quality control.

Statistical analysis

The significance of difference between the reference uncontaminated aliquots and those containing different degrees of K2EDTA contamination was evaluated with Wilcoxon’s matched pairs test. The mean (percentage) bias was also assessed with Bland and Altman plots, and then compared to the desirable quality specifications for bias provided by Ricos et al. (14). The concentration of the different parameters was reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas the bias was calculated as mean and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Table 1. Volumes used to obtain different degrees of K2EDTA blood volume contamination.

Results

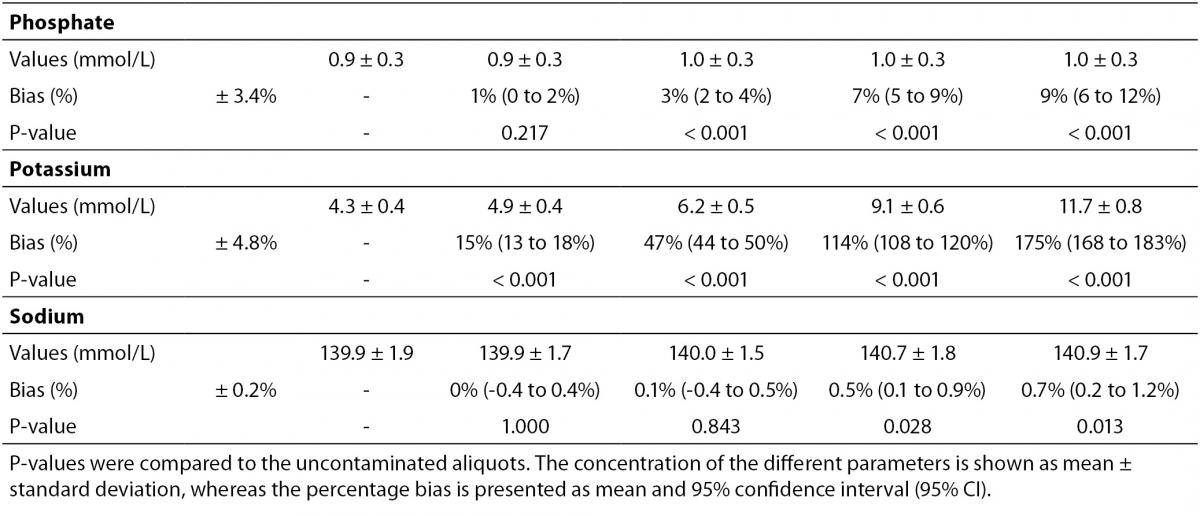

The main results of this study are shown in table 2 and figure 1. A statistically significant variation starting from 5% K2EDTA contamination was observed for calcium, chloride, iron, LD, magnesium (all decreased) and potassium (increased). The variation of phosphate and sodium (both increased) became statistically significant with 13% and 29% K2EDTA contamination, respectively. The values of ALT, bilirubin, creatinine and lipase remained unchanged up to 43% K2EDTA contamination. When the variation was compared with the desirable quality specifications, the bias appeared to be significant for calcium, chloride, LD, magnesium and potassium (starting from 5% K2EDTA contamination), sodium, phosphate and iron (starting from 29% K2EDTA contamination) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effect of different degree of lithium heparin with K2-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) blood volume contamination on alanine aminotranspherase (ALT), bilirubin (total), calcium, chloride, creatinine, iron, lactate dehydrogenase (LD), lipase, magnesium, phosphate, potassium and sodium. The percentage bias is shown as mean and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The dotted lines delimit the desirable quality specifications for bias.

Discussion

The results of our experimental investigation provide a precise bias estimation of K2EDTA blood volume contamination when performing a large panel of clinical chemistry tests. The dramatic bias in the measured concentration of calcium, magnesium and potassium (Figure 1) occurring after a very modest K2EDTA contamination (i.e., < 5%) provides additional evidence in support of the need to implement reliable phlebotomy guidelines, along with developing specific training programs for healthcare phlebotomy staff aimed at reducing preanalytical errors (15-18). We also observed that the concentration of phosphate and sodium was affected, but the bias became clinically significant over 13% K2EDTA blood volume contamination. The different bias observed on each analyte probably mirrors the different attraction-force degrees between chelating agent (i.e., EDTA) and metal ions (i.e. Ca++, Mg++, Fe+++) (19). Briefly, chelation entails the generation of two or more separate coordinate bonds between a polydentate (multiple bonded) ligand and a single central atom. It is also noteworthy that the EDTA salts have different degrees of ionization (20). In our study we used vacuum tubes containing dipotassium EDTA (K2EDTA) formally known as 2-({2-[bis (carboxylatomethyl)azaniumyl]ethyl}(carboxylatomethyl)azaniumyl)-acetate dihydrate, 2K+ · C10H14N2O82- · 2H2O. From a genuine chemistry perspective, whole blood is composed of an aqueous liquid (i.e., plasma), in which corpuscular elements (i.e., blood cells and platelets) are suspended. In whole blood, K2EDTA dissociates in two K+ plus one C10H14N2O82-. Consequently, this free carboxylic acid form strongly chelates divalent metal ion (i.e. Ca++ and Mg++) but less powerfully interacts with transition metal ions such as Fe+++ (19). Additional, nonmetal elements such as Cl- and P3-, which are incapable of forming simple positive ions in solution, do not interact with EDTA. Phosphorus is measured from phosphate (PO43−) on Roche cobas 6000 c501 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) (21). As such, our data (Table 2 and Figure 1) seems in agreement with the aforementioned theory. The statistically significance observed for Cl-, PO43−, and Na+ probably reflects both situations: i) osmoses effect as a result of K+ dissociation from K2EDTA; ii) generation of sub products (i.e. KCl, NaOH, H3PO4, PO4Na3) after both Ca++, Mg++ and Fe+++ chelation process. This would finally explain why the significant variation observed for Cl-, PO43−, and Na+ is not directly correlated with the EDTA chelating force.

The identification of serum or lithium heparin sample contamination by EDTA salts is often challenging and may seriously jeopardize both the clinical decision-making and patient safety. The presence of K2EDTA or K3EDTA in serum or plasma specimens may mask true cases of hypokalaemia or hypercalcaemia, whereas true cases of hypokalaemia may be misjudged as significant hyperkalaemias (12). Hyperkalemia is a medical emergency requiring urgent intervention to prevent unfavourable outcomes, which are mainly represented by perturbations of cardiac rhythm (22). It is hence important that potential causes of spurious potassium elevation are ruled out, to prevent the administration of potassium-lowering therapy in otherwise hypokalaemic or normokalaemic subjects. Similar conclusions can be drawn for spurious decreases of calcium and magnesium, which may also trigger unjustified panic and inappropriate treatment (23). According to this evidence, the serial measurement of EDTA in hyperkalaemic, hypocalcaemic and hypomagnesaemic samples in order to exclude EDTA salts contamination may be regarded as another potential strategy for safeguarding patient safety, since serum EDTA assays are inexpensive and easy to set up on automated analysers (11).

Table 2. Effect of different degree of lithium heparin blood contamination by K2-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) on alanine aminotranspherase (ALT), bilirubin (total), calcium, chloride, creatinine, iron, lactate dehydrogenase (LD), lipase, magnesium, phosphate, potassium and sodium.

Some previous epidemiological studies investigated the effect of EDTA salts contamination on different panels of laboratory tests. Davidson assessed a large number of lithium heparin specimens received from inpatients, outpatients, and general practices throughout the local area (12), and reported that the analytes mostly biased by the presence of K3EDTA were calcium (-100%), magnesium (-100%) and unsaturated iron-binding capacity (+335%). Additional effects could be appreciated for bicarbonate (-17%), LD (-14%), creatine kinase (CK; -61%), amylase (-34.3%) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP; -70.5%). Both aspartate aminotranspherase (AST) and ALT were virtually unaffected by EDTA contamination. In a subsequent study, Sharratt et al. analyzed the potential K-EDTA contamination (it was not specified whether K2 or K3 were used) in as many as 12,895 serum samples (11), and found that the concentration of EDTA was negatively correlated with that of calcium (r = 0.673; P < 0.001), zinc (r = 0.424; P = 0.017) and magnesium (r = 0.551; P = 0.001), while it was positively associated with that of potassium (r = 0.554; P = 0.001). In agreement with the epidemiological data of Davidson (12), we failed to find substantial variations of ALT, as well as of bilirubin, creatinine, lipase up to 43% K2EDTA contamination. This is noteworthy because, despite it is widely accepted that unsuitable samples (24,25), including those contaminated by external fluids or additives (26), should not be analyzed and results suppressed, the variations observed in these four common parameters remained clinically acceptable, so that the single laboratory may decided whether test results in samples with as much as 43% of K2EDTA contamination may reported or not to the requesting physicians. It is also noteworthy that the EDTA tubes may be occasionally underfilled, so that the final concentration of K2EDTA would be much higher and the effect would be different, probably more significant.

One limitation of our study was that we did not evaluate the impact of contamination to with K2EDTA blood volumes lower than 5%, since the introduction of very small amounts of blood (i.e., lower than 50 µL), may lower the accuracy of dilution due to the intrinsic viscosity of whole blood. Moreover, the bias emerging from sample contamination with small amounts of EDTA blood volume transferred by backflow during blood draw was previously tested by others, and the outcome was rather heterogeneous (3-6,8,9,27-30). It is also important to mention here that our results were generated using vacuum tubes from a single manufacturer, so that they may not be directly transferable to other brands (31,32). Indeed, additional studies may be needed to define the impact of contamination with K2EDTA blood volumes lower than those that we have tested.

The concentration of K2EDTA (i.e., from 0.09 to 0.77 mg/mL) used in our experimental investigation (Table 1), is also commonplace in blood samples drawn from inpatients undergoing chelation therapy. This treatment is based on multiple infusion (e.g., weekly) for the treatment of coronary and peripheral artery disease (33). Each chelation infusion contains up to 3 g of EDTA (33). Therefore, in agreement with our data, the possibility that EDTA-based chelation treatment may interfere with laboratory testing should not be discounted.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of our investigation attest that concentration of calcium, magnesium, potassium, chloride and LD is dramatically biased by even a very modest K2EDTA contamination (i.e., 0.09 mg/dL). The values of iron, phosphate, and sodium are still reliable up to 0.51 mg/dL K2EDTA contamination, whereas ALT, bilirubin, creatinine, and lipase appeared to be less significantly biased by K2EDTA contamination. This experimental investigation may hence provide general information about the potential effect of K2EDTA blood contamination of lithium-heparin tubes, which may be useful to quality laboratory managers for establishing local policies for sample rejection and/or test results suppression.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Monica Voi, medical technician from the clinical chemistry section, for her skillful technical support. Special thanks to Ms. Sandra Meneghelli, quality manager.